So this is Substack. This right here, what you’re reading, was written (in Google Docs) and pasted into the Substack interface, then sent to your email address which is kept in Substack’s servers. If I get some new sign-ups on the back of this piece, those email addresses will be securely filed away by Substack. And if the planets align and I ever turn on paid subscriptions, all the business will handled by Substack.

That is what Substack does. And Substack is supposedly worth $650m USD, about half the market cap of Air New Zealand.

How does a company with just 50 employees based on decades-old email newsletter technology become that hot?

It’s all about who you work for. Substack works for writers.

If you are not already a subscriber, please consider signing up.

Hamish McKenzie is 39, was born in New Zealand’s South Island, is married to an American, has two kids and is temporarily in Wellington sitting out COVID.

He’s a journalist who moved to Silicon Valley and got sucked into the machine that turns ideas into mad numbers, got to know Elon Musk, and started a company with two colleagues.

Along the way he managed to transmute his love of writing into a platform that offers some writers that ability to make a living. For a very select few, Substack is a gold mine: the top 10 writers make more than $20m USD as a combined total.

The company is privately held, so there’s not huge transparency around the numbers. But it’s safe to say millions of people read Substack newsletters, and tens of thousands write them. McKenzie tells me more than 500,000 people pay money for their subscriptions. Substack has raised over $50m USD in its funding rounds and big names like Andreessen Horowitz are on board.

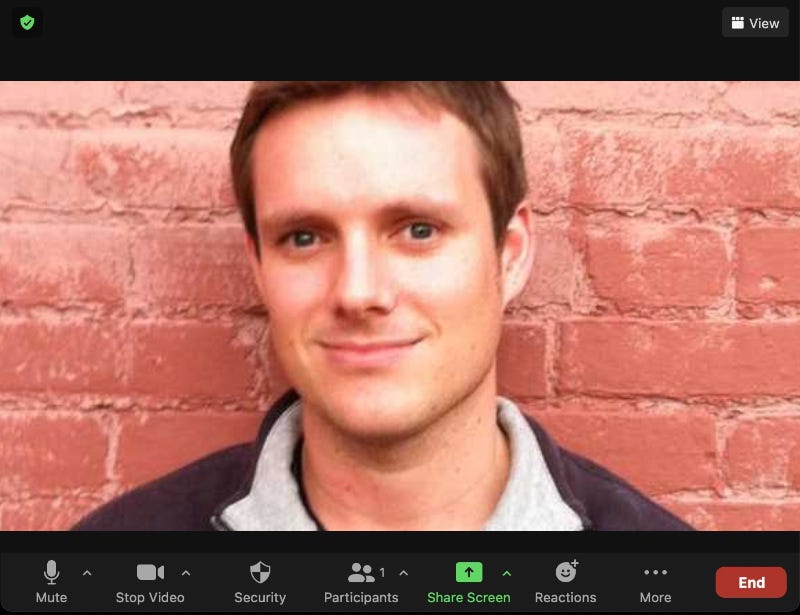

I speak to McKenzie over Zoom: he’s in a meeting room borrowed from Stuff for the hour, I’m in my home office south of Sydney. His kids are young, he’s in the nappy zone, and he’s got that new parent pallor. A gray tinge. He’s probably doing conference calls at all hours too.

As with most interviews, McKenzie is doing me a favour. He takes on risk - that he’ll say something rash, or I’ll frame him - for the small return of publicity. I don’t think McKenzie wants it, and Substack definitely doesn’t need it.

Unbreak my ecosystem

“What we're trying to do is unbreak the media ecosystem, by taking the power away from these big platforms oriented around engagement-based algorithms, and putting that power instead in the hands of writers and readers. So in that world, rather than writers and readers being owned by platforms, they can be the owners of the platforms.”

McKenzie speaks my language, and as opposed to the fuller account of this interview on The Spinoff, that’s what this post is about. It’s about how and why Substack appeals to me. Substack works because Substack talks about writers and writers talk about themselves. Substack is a self-marketing product.

Back in the Share Wars days, we discovered that articles about Facebook did very well on Facebook. And as Andy Hunter wrote in “All Your Friends Like This”, after the telegraph was invented, the telegraph was its own best marketing device. Communications media speak of many things, and one of their favourite topics is themselves.

That’s what this post is: an exercise in self-referential marketing.

Against the social winds

There are also some things Substack doesn’t do that are part of the success.

“Substack is a platform that does not try to shove views down your throat against your will. You as the reader have the power to control and build your own content experience … it also helps to free writers from that mode where they get rewarded for inflammatory stuff, for stoking conflict.”

The Substack content guidelines forbid hate speech, fraud, porn and some other nasty content, but they don’t forbid arguments against the prevailing social winds and accepted beliefs. This has put it in the cross-hairs for, for example, allowing Father Ted writer Graham Linehan to have a newsletter. Linehan was kicked off Twitter for statements about transgender people.

I haven’t investigated all the alleged offences by Substack writers - which include some Covid misinformation as well as the Linehan-like stuff - but it feels like social and intellectual intolerance to insist that these voices not be allowed at all. McKenzie believes the atmosphere of aggressive protest has been engineered by an earlier generation of Silicon Valley companies.

“I blame social media for creating a distorted view. We’ve lived through this period now where these AIs have dominated the media ecosystem based on engagement-based algorithms. News feeds from social media amplify and reward the kinds of content and behaviour that keep us piqued and turn us against each other and erode trust and understanding.”

He asks me to consider how Donald Trump would have fared politically without Twitter. Would he have been president without a platform that “almost uniquely rewarded his style of engagement and mode of discourse”?

“People are exhausted and skeptical about the roles that digital media platforms play because the last 10 years has been a total shit show. And so I think Substack is the antidote to that stuff.”

A writer’s platform prepares for war

The reason the guy is so convincing about writers, and his company’s secret sauce in terms of appealing to writers, is that he is a journalist and a writer himself. What founders know and who they are matters. Most tech companies are founded and run by developers, which is partially true of Substack - McKenzie’s co-founders Chris Best and Jairaj Sethi are developers - but McKenzie’s experience is essential.

It’s noticeable to me that Substack’s corporate language is different from other tech companies. It’s all about “writers” and “readers”, rather than content or product. This, again, is about fitting the business to its clients, and will stand it in good stead in the coming newsletter wars.

Twitter already has a newsletter product, and Facebook is on the verge of launching its Substack competitor, Bulletin. Seeing how Substack fares against the might of Zuckerberg’s social network will be intriguing. While Facebook has incredible engineering and marketing power, and can promise writers an audience and money they may struggle to get on Substack, it has some handicaps.

As Facebook moves into an editorial area - choosing writers to support - it has decided to stick to less socially divisive topics such sport and fashion. At this stage, it will launch only with approved writers. Content is a different game, and traditionally big successful platforms have kept it at arm’s length. It’s messy work, and it doesn’t scale. To date there is no algorithmic “solution” for content, and that makes it an alien domain for tech companies.

McKenzie is fervent in his belief that Substack is making a better world for writers, and he says he doesn’t care about the competition.

“[The arrival of newsletter competition] is all good. What we're trying to do is … subvert the attention economy. Anything that gives writers more options and more ways to make money is good. We’re not focussed on the competition, but on building the Substack ecosystem as as strong and powerful as it can be.”

It certainly feels like he’s sincere when he says that. It will be put to the test if the global big boys tear up the platform he put so many late nights into building.

If you appreciated this post and are not already a subscriber, why not sign up?

Real Hovels of News: Cigarettes and Imperial 66s

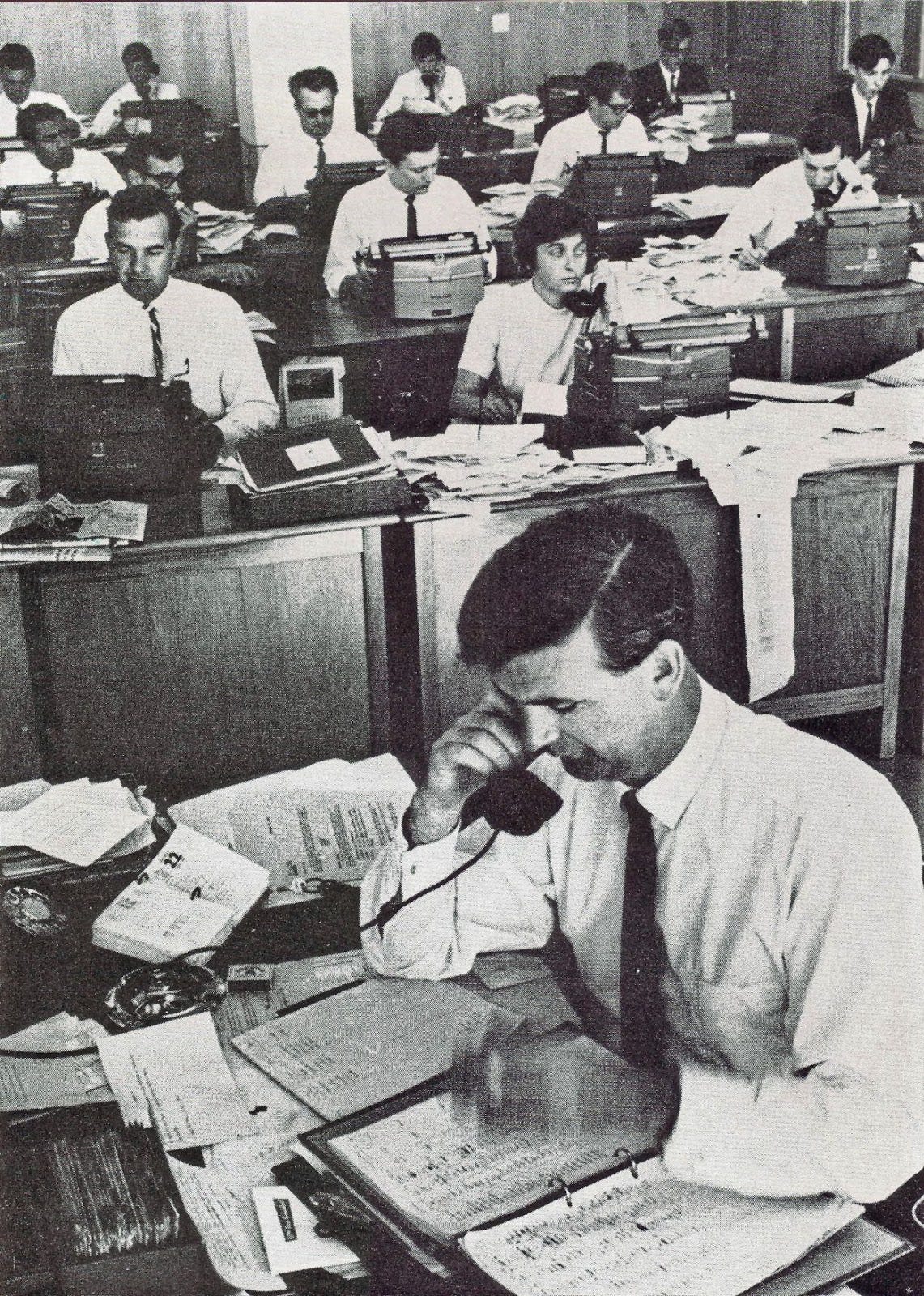

Media sage and consultant colleague Gavin Ellis, the former editor-in-chief of the New Zealand Herald, sent in this classic hovel picture from more than 50 years ago. Thanks Gavin.

This is the New Zealand Herald reporters room in 1966-7. In the foreground is chief reporter (NZ equivalent of the Australian chief of staff) Gerry Symmans who later became press secretary to Prime Minister Robert Muldoon. Reporters’ desks were jammed close together — reporters were all at their desks for the photograph but on an average day some would have been out on assignment and others braving the staff cafeteria lovingly dubbed The Greasy Spoon.

The pervasive atmosphere was cigarette smoke (note the ash tray on Symmans’ desk). There was hardly a desk that didn’t have the scars of forgotten fags burnt into the varnish. The Imperial 66 typewriter was the standard issue weapon.

The picture is from “The New Zealand Herald Manual of Journalism" edited by the late John Hardingham, who went on to become one of the paper’s finest editors. In a chapter of the book on the flow of news, Hardingham wrote “Of all the problems associated with newspaper production, none is so forbidding as the daily challenge of compressing a quart of raw news into a pint pot of space.” Half a century has passed and, irrespective of the medium, nothing has changed on that score.