In a week of great importance for our future, I’m going to consider what we knew about the future 60 years ago. The 1964 Rand Corporation “Report on a long-range forecasting study” consulted experts in many different fields and compiled their predictions on six broad areas: population, science, automation, space, weapons and war. I read about the report years ago - thanks to the excellent Benedict Evans - and at that time resolved to present the predictions in a way that was easier to read. That’s what I’m doing today.

Because I am obsessed with technology and news media, I have chosen to focus on predictions related to those areas. Here are some takeaways:

The experts were too optimistic. For predictions that have come to pass, median prediction dates were on average 15 years early. Most haven’t happened at all.

The authors emphasise “automation” over computation, which seems weird now. Computers are less prominent than you would expect.

The importance of digital networks is missing.

This lack of foresight on networks leads, ironically, to a correct prediction: the availability of newspapers and magazines in the home in 2005

I think the report is interesting in its own right, but I’m also mindful what it can teach us about our own future: we are undoubtedly too optimistic on timelines, most of what we think will happen won’t, and we are probably missing the main point.

Stepping into the past

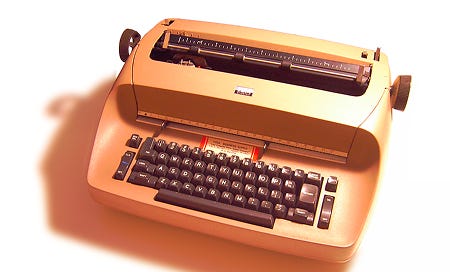

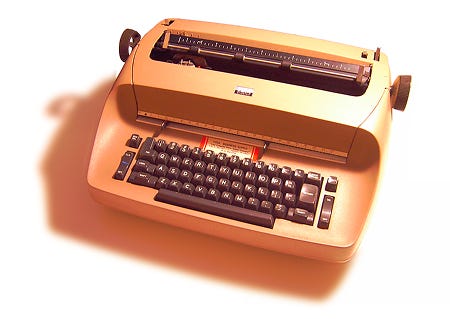

To read the report is to step into a time machine. The font is monospaced Courier, and was probably typed on an IBM Selectric typewriter (pictured top). Graphs are hand-drawn, and the whole document feels authentically janky, with some pages slightly skewed and the occasional correction using what looks to be Liquid Paper. Despite the hand-made construction, it’s solid. Ted Gordon and Olaf Helmer*, the authors, were clearly intelligent people who knew the majority of the predictions were going to be wrong. They make it clear the report is primarily an experiment in forecasting itself.

The Rand Corporation - often written RAND (for “Research And Development”) - is the world’s original think-tank, set up in the late 1940s by the US Air Force and then incorporated as a non-profit in 1948. Rand made its reputation with reports such as “Viet Cong Motivation and Morale in 1964”. That document evokes scenes of intelligence gathering in gritty, war-torn Vietnam. It offered insights that changed the course of the war.

Strange how comfortable the past can be, despite the brutality and tumult. The forecasting report fills me with nostalgia for a time I never experienced - golf-ball typewriters, smoking in offices, and a super-power trying to divine the future on graph paper.

The anxieties and hopes of the 1960s are documented in the predictions of the experts. There’s the chance of a global war, mass starvation, and the promise of nuclear fusion reactors. We’ve had none of them. Although I’m not going into it here, I note the experts got population growth wrong. They just couldn’t imagine there would be enough food to feed 8 billion people by the 2020s, which was where their projections were headed. So they said we’d only have 6 billion. But the projections were right after all. We reached 8 billion in 2022, with no widespread starvation.

The tech predictions

The table below shows 20 predictions I have distilled from the Automation and Science sections of the report. The entire combined set of predictions (55) are linked at the bottom of the newsletter. I have used my judgement in determining whether the prediction has been achieved and included an approximate date for that achievement.**

You’ll notice straight away the big discrepancy: the experts believe they’ll have automated translations in a mere eight years time (1972), but that it would take 41 years to have newspapers and magazines transmitted to homes (2005). The first speaks to underestimating the complexity of translation and overestimating the abilities of early computers. The second implies that information transmission and quality home printing are much more difficult achievements. This is odd. In reality, network speeds increased exponentially from 1964, making the transmission of full-resolution newspapers and magazines possible in the 2000s. High quality home printing was available with inkjet technology and the release of affordable printers like the Apple Stylewriter in the early 1990s.

An even bigger predictive error is the failure to anticipate the proliferation of screens in everyday life. In 1964 most homes had a single TV set. In 2024, high-resolution monitors are everywhere.

Now take a look at the whole picture painted by the predictions. Years before newspapers and magazines are faxed to homes, there are robot servants and doctors, granular democracy, a universal language, nuclear fusion, self-driving cars, and major political decisions being made by computer. While the experts had anticipated social dislocation from automation - with mass unemployment and the eventual introduction of universal basic income - they didn’t consider an information revolution and its profound impacts.

Systemic changes to news media are not even on the radar. After 40 years of breathtaking progress in this 1964 future, there’s still the same old newspapers and magazines, printed out at home. There is no hint of universal, zero-cost publishing or how that would lead to social networks and the breakdown of institutional authority.

Media theory was in development in 1964 - it was the same year Marshall McLuhan published “Understanding Media”, with his revolutionary idea that information technologies change societies - so at least some people knew the importance of networks. But it was a world where authority was constructed and constrained by strictly limited access to publishing/broadcasting. Perhaps none of the experts took the new theories seriously enough to consider what would happen when the constraints disappeared.

Another major blind spot for the experts and authors of the 1964 report is climate change. Global warming from increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide was already understood, and in 1965 a US government report clearly spelled out the risk. But there are no predictions at all regarding the environment/climate or related technology, beyond weather manipulation.

What was right

These predictions were not science fiction. They were what many respected experts believed would most likely happen.

The predictions for the first decade all happened (see full list below), and several others seem to be half-way there now. For example, self-driving cars and automatic rapid transit systems have been partially achieved. “Man-machine symbiosis” is also close to real. It’s not as imagined, not nearly as glorious, but with mobile phones we have a pervasive presence that approaches symbiosis. I don’t like being without my phone. How about you?

I wouldn’t include thermonuclear power or servant robots in the “nearly there” category. We’re still years out. Some things just take a really long time.

What are we missing?

Despite the recent rapid developments in Large Language Models and other generative AI, the lesson from the Rand report is that Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) and other super-intelligent agents are probably further away than we think. On average, the 1964 experts were 15 years out. That’s how long you should be adding to any new long-term predictions you see.

There is already evidence that LLMs are hitting walls - data, power, compute - that may mean the years of rapid progress are behind us. Also, even with continued improvement, we have to recognise that LLMs are currently flawed in ways that are not easy to correct. In my experience, they are factually unreliable. I regularly catch NotebookLM and ChatGPT being wrong about simple things, and the magic is wearing off. I no longer believe the developers really know how to deal with this.

The big question for us: what is the main point we are missing?

We anticipate AGI and the runaway progress that might entail. We have cheaper access to space. We have the beginnings of compelling virtual worlds. There are major advances coming in genetic manipulation and medicine. We are aware of the problems of climate, misinformation, political division, anti-authority, and anti-democracy.

This is stuff we know about. What is our equivalent of Helmer and Gordon missing the consequences of the digital information revolution?

Just as knowledge about media influence and climate change was around in 1964, so knowledge about our blind spot is undoubtedly already with us. We just don’t recognise it. Conversely, some things we take for granted now will certainly be heading for irrelevance. Like newspapers in 1964.

Here is the full list of Automation and Science predictions.

Let me know if you have any trouble reading the prediction tables. I have other formats available.

Have a great weekend

Hal

*The authors were both very long-lived. Theodore “Ted” Gordon, lived to 97. He died this year (2024). Olaf Helmer, lived to 100, dying in 2011.

** The dates are the median expert predictions of a 50% chance of achievement. On some questions there was big timing variation, something captured in the original graph. I’ve chosen the median as a consensus. Around 25 experts were consulted for each topic, although not all responded.

Probably right Jono. The potential is there. Is it actually happening wholescale? Probably actually.

"The big question for us: what is the main point we are missing?" we are missing incentives and disincentives built into the protocol stack. Only that way can we develop digital networked ecosystems that balance risk and are generative and sustainable. Today's networked ecosystems (including AI) are not sustainable. Humanity needs to build networks that resemble those found in nature.